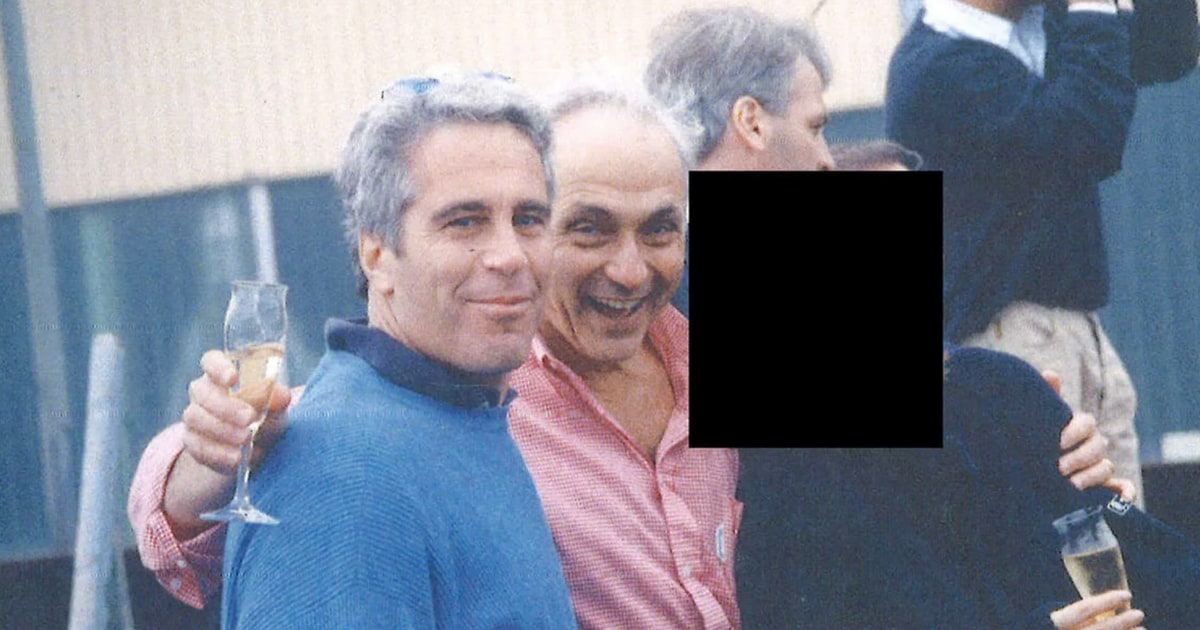

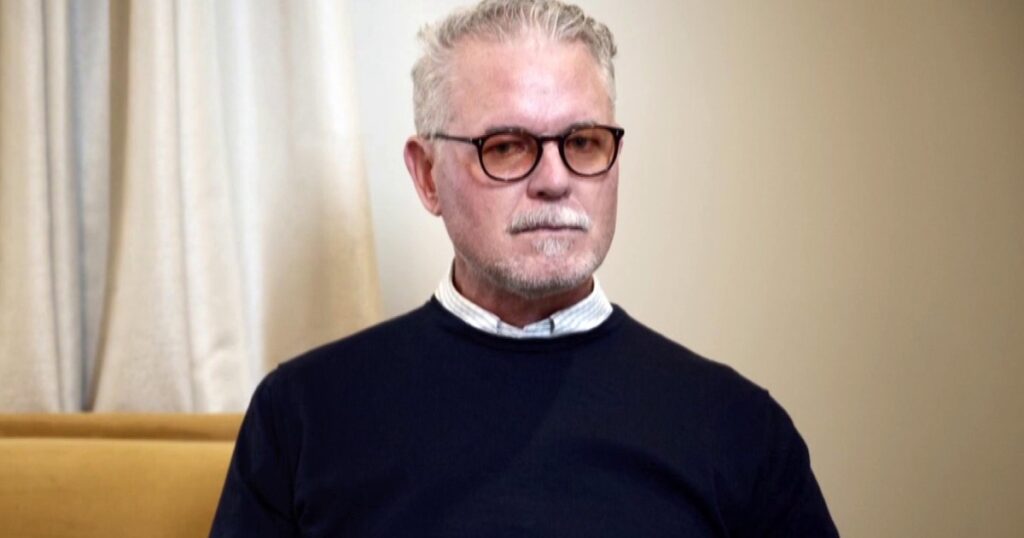

NEW ALBANY, Ohio — Around the time he began taking financial advice from Jeffrey Epstein, Ohio’s richest man made a fateful investment.It was 1990, and Leslie Wexner, whose retail clothing empire included brands like Abercrombie & Fitch and Victoria’s Secret, put $100,000 behind Republican George Voinovich’s successful campaign for governor.The contributions opened doors that Wexner had sometimes struggled to walk through while attempting to translate his philanthropy and success in business into civic and political power in his home state.Aided by his new friends in the Voinovich administration, Wexner developed this once-small town into an exurban enclave around his mansion. Helped along by a state-funded highway interchange, he built an upscale Columbus shopping mall anchored by his stores.“George used to say, ‘We need to do more with less,’” said a longtime Republican operative and Voinovich ally, recalling the late governor’s reputation for frugality. “We used to say that was a double entendre: ‘Do more for Les.’”Wexner’s relationship with Voinovich also planted the seeds for a coalition of CEOs that is credited with shedding Columbus’ image as a Midwestern backwater. Meanwhile, Wexner continued his charitable giving toward pro-Jewish causes, education and other public policy areas — adding to a legacy that put his name on a hospital, art gallery and football training complex at his alma mater, Ohio State University.But that legacy is now in jeopardy, given Wexner’s association with Epstein, the late sex offender who in 2019 was found dead in his prison cell while awaiting trial on federal sex trafficking charges. The specter of Epstein hovers over Columbus and especially nearby New Albany, where, records show, Epstein owned property and had a senior role in Wexner’s development firm in the 1990s. Epstein, in the words of his co-conspirator Ghislaine Maxwell during a Justice Department interview last year, “ran New Albany.”“I really believe this guy [Wexner] did 50 years of amazing stuff for Columbus,” said a GOP strategist, who, like many of the 20 people who spoke with Jattvibe News, was granted anonymity to share candid assessments of Wexner. “If you’d have said in 2014 that in 12 years we would be here, I’d have said you were f—–g crazy.”Rep. Robert Garcia, D-Calif., the ranking member of the House Oversight and Accountability Committee, speaks as fellow committee members look on at a news conference in New Albany, Ohio, on Wednesday.Dustin Franz / Bloomberg via Getty ImagesThe fallout has engulfed not only Wexner, but also his allies and admirers in Columbus and the community he made here, essentially, from scratch more than 30 years ago. Members of the House Oversight Committee investigating Epstein traveled to New Albany this week to depose him. There also are calls to pry Wexner’s name off the buildings at Ohio State, where he served two stints as a trustee. And in recent days, politicians who once accepted Wexner’s cash for their campaigns for Congress all the way down to the Columbus City Council have scrambled to distance themselves.“He was one of the city elders of Columbus,” said another longtime Republican strategist in the state. “He shaped the future of the city for the better, there’s no doubt. But when you talk about legacy, people tend to forget that because of the more salacious stuff.”Wexner, 88, has said he met Epstein in the mid-1980s and eventually hired him to manage his money. He also has said he cut ties with Epstein in 2007, after Epstein was accused of sexually abusing minors in Florida. Around that time, Wexner wrote in a letter issued by his foundation in 2019, “we discovered that he had misappropriated vast sums of money from me and my family.”Wexner also has denied any knowledge of an allegation made by Epstein survivor Maria Farmer, who said in a 2020 lawsuit against the Epstein estate that she was assaulted in 1996 by Epstein at an Ohio property “owned and secured” by Wexner and his wife, Abigail Wexner.“I was naïve, foolish, and gullible to put any trust in Jeffrey Epstein,” Wexner said in a statement submitted to the House Oversight Committee at his deposition Wednesday. “He was a con man. And while I was conned, I have done nothing wrong and have nothing to hide. I completely and irrevocably cut ties with Epstein nearly twenty years ago when I learned that he was an abuser, a crook, and a liar. And, let me be crystal clear: I never witnessed nor had any knowledge of Epstein’s criminal activity. I was never a participant nor coconspirator in any of Epstein’s illegal activities.”Scrutiny of Wexner’s relationship with Epstein has intensified in the months since Congress required that the Justice Department release Epstein-related files. Wexner was called an Epstein co-conspirator in a 2019 FBI document released last week and mentioned as a possible co-conspirator in a previously released FBI email from that same year. A Wexner legal representative has said that Wexner had been informed in 2019 by an assistant U.S. attorney that he was “neither a co-conspirator nor target in any respect.”As new details have emerged, politicians across the state have been under pressure to rid their campaigns of the money Wexner gave them.Rep. Joyce Beatty, one of the few Democrats outside of Columbus city government to whom Wexner had donated with regularity, last week said she redirected all contributions received from him to groups that support victims of sex trafficking and abuse.“If he participated in or enabled these crimes, he must be held accountable to the fullest extent of the law,” said Beatty, whose district includes Wexner’s home.State Treasurer Robert Sprague, a Republican candidate for Ohio secretary of state this year, sent a donation matching the $23,000 that Wexner and his wife had given to him in 2022 to a local housing services organization. Dalton Throckmorton, Sprague’s campaign manager, cited “the increasingly disturbing reports concerning Les Wexner.”Meanwhile, Wexner money is destined to be an attack line in Ohio’s closely watched Senate race. Sen. Jon Husted, the Republican who was appointed to the seat last year, received a $3,500 contribution from Wexner in July. Husted’s earlier campaigns for state office received tens of thousands of Wexner’s dollars.Sen. Jon Husted, R-Ohio, received a $3,500 contribution from Wexner in July.Bill Clark / CQ-Roll Call via Getty Images“Ohioans deserve to know why Husted chose to protect a pedophile and his billionaire donor instead of standing with the victims,” former Sen. Sherrod Brown, the Democrat running against Husted this year, said in a statement that referenced Husted’s vote last September against releasing the Epstein files. A Brown campaign representative said Brown has never taken money from Wexner.Husted, who later joined a unanimous Senate vote to release the files, “has directed the campaign to donate Wexner’s money to charity,” said his Senate campaign spokesperson, Tyson Shepard, who did not have information about whether that includes money from Husted’s state account, which last month reported a balance of more than $6 million. Others have declined to relinquish Wexner money. Sen. Bernie Moreno, an Ohio Republican who received $3,500 from Wexner in June, did not solicit the donation and has no plans to return it or redirect it to charity, a person familiar with his campaign said.Moreno, a former car dealer who was elected in 2024, is the rare newcomer to Ohio politics who has received money from Wexner while aligning himself tightly with President Donald Trump.None of the more than $4.3 million that Wexner has contributed to federal campaigns and committees since 1980 has gone to Trump, according to Federal Election Commission filings. Wexner also has never donated to Vice President JD Vance, who in 2022 won a Senate seat in Ohio with Trump’s endorsement, or to businessman Vivek Ramaswamy, the Trump-backed candidate for Ohio governor this year, FEC and state campaign finance records show.Wexner, a Trump critic, announced that he was no longer a Republican in 2018, the year before his Epstein ties filtered back into public. His contributions to GOP candidates slowed — but they did not end. Some younger operatives picked up on how Wexner’s giving was at times offset by donations from his wife, a generous contributor to Democrats. And they began to wonder if Wexner’s money was more trouble than it was worth.“Once Wexner left the party and went Never Trump, people really cooled on him,” a former Republican state lawmaker said. “And then you had the Epstein stuff.”’Les the mess’CEO Les Wexner speaks at an annual investor meeting for L Brands in Columbus, Ohio, in 2014.Adam Cairns / Columbus Dispatch via ImagnYou have to go back nearly 40 years to find the last time Wexner resembled anything remotely close to an outsider in Ohio.The Limited — his apparel chain that eventually would grow to include Bath & Body Works and other household names — made him a frequent subject on the business pages and put him on the cover of New York Magazine in 1985. But the elites in Columbus were still trying to figure him out, and Wexner puzzled over how to work his way into their circles.A Boston Globe profile in 1989 referred to him as a “Jewish Rockefeller” while quoting an unidentified person “friendly with Wexner” who observed that he had “not learned to be a team player.” He was known “affectionately,” this person added, as “Les the mess.”Wexner could have decamped to New York, where much of his business was done. But doing so would make him “one of many,” observed another longtime GOP operative familiar with Wexner’s political and philanthropic work.“He’s basically a shy person and that probably intimidated him,” this person added. “Staying in Ohio, and Columbus specifically, allowed him to have a much greater — and positive — impact and also be the biggest fish, albeit in a much smaller pond.”Politics became his gateway. In the ’80s, Wexner had backed two of Ohio’s most prominent Democrats: Gov. Dick Celeste and Sen. John Glenn. And while Wexner was doing just fine for himself — he had cracked the inaugural Forbes 400 list of richest Americans in 1982 — the Republican Voinovich would help usher in his Columbus Renaissance.A former mayor of Cleveland, Voinovich encouraged Wexner to become more civically engaged by connecting him with a group of upstate business executives known as Cleveland Tomorrow, Wexner recalled in a 2015 interview with Columbus CEO. Their organization became a model for Wexner as he worked with others to launch the Columbus Partnership, which since 2002 has been a key player in the region’s growth.Voinovich also smoothed the way for Easton, the high-end lifestyle center that Wexner had dreamed up as a showcase for his stores. With Wexner’s company chipping in a reported $18 million in cash and land, the state backed construction of a $235 million highway interchange that leads to the mall, which opened in 1999.A city rises out of nowhereAn Intel chip-manufacturing facility in New Albany last year. Doral Chenoweth / Columbus Dispatch via ImagnNew Albany was the other endeavor that ratified Wexner’s status as an Ohio power broker — in some ways more so than anything else he accomplished.When he began drawing up the plans, it was a rural village of barely 1,000 people. Today it’s a fully formed suburb with a population of more than 11,000 living in neighborhoods of Georgian-style redbrick homes tucked behind gleaming white picket fences. Wexner’s spread — valued at nearly $50 million, according to county property records — hulks alongside a country road, with a gated entry built into a hollowed-out white barn.Abercrombie & Fitch, which The Limited spun off in 1998, remains headquartered here. Meta, the parent company of Facebook, has a data center nearby. And Intel is at work on a massive semiconductor factory, though the project has been delayed.So many of these developments trace back to Wexner’s jump-start during the Voinovich years, with the administration, as it would do for Easton, funding infrastructure improvements. Several operatives from those days recalled Wexner’s all-out effort to secure a liquor license for the country club that would anchor a new housing development.After voters rejected the permit, lobbyists working on Wexner’s behalf — and with a top Voinovich aide’s support, The Columbus Dispatch reported — quietly drafted legislation that would have expedited a new vote on the issue. Voinovich vetoed the measure after the local newspaper uncovered how it would benefit one of his top donors. But Wexner quickly found another loophole: By opening a microbrewery at the country club, he was able to obtain a liquor license allowing the sale of other alcoholic beverages.In a written statement to Jattvibe News, New Albany Mayor Sloan Spalding praised Wexner and his development firm for the city’s “careful planning” and “progress.”“The New Albany Company, established by Les Wexner, has been a key figure in this journey, greatly influencing early city development and infrastructure with its leadership and resources,” said Spalding, who was elected in 2015. “Mr. Wexner’s vision for a thoughtfully designed and distinctive community is reflected in what New Albany has become today.”A ‘Wizard of Oz’ characterThe gated entrance to Wexner’s property in New Albany in 2022. Doral Chenoweth / USA Today Network via ImagnWhen a term-limited Voinovich moved on to the Senate, Wexner remained politically engaged at high levels. He briefly jumped back across the aisle in 2005 to support the early days of then-Columbus Mayor Michael Coleman’s campaign for governor. But Coleman dropped out before the Democratic primary and Wexner kept a lower profile in the following year’s general election — the last time a Republican lost a race for governor in Ohio.Wexner also was slow to warm to Republican John Kasich’s bid for governor in 2010, four operatives involved with that campaign recalled. He sought to make nice after Kasich won, presenting him with a 5-foot pencil inscribed with a Wexner mantra: “Keep the main thing the main thing.”“It was some kind of symbolic gesture, like, ‘You’re in charge now,’” a person who witnessed the meeting said. “I recall interpreting it as a mild, humoristic mea culpa.”Kasich and Wexner eventually found common cause, both during Kasich’s two terms as governor and in their mutual disgust with Trump’s takeover of the Republican Party. In 2023, Wexner gave $100,000 to the political action committee that Kasich and his team kept alive after his unsuccessful run for president seven years earlier. Kasich did not respond to questions about the donation.Meanwhile, younger Republican operatives in Ohio treat Wexner as a curiosity and describe him as something of an anachronism whose influence is nonetheless still felt.“I’ve never even seen Wexner, much less met him,” said one person who has worked for some of the state’s top Republicans since 2016. “Kind of a ‘Wizard of Oz’ character.”These are far from the days of “More for Les.” Wexner stepped down as CEO of L Brands, the outgrowth of his Limited empire, in 2020 as Victoria’s Secret and Bath & Body Works split off into separate companies and early whiffs of the Epstein scandal swirled around him. He resigned as chair of the Columbus Partnership a year later.“I honestly don’t know how often he is here,” said a Columbus-area community leader who praised Wexner’s efforts with the Partnership. “I don’t know where he is physically. I’ve heard all kinds of things. I don’t know what’s true, what’s not true.”The unknowns weigh on those dismayed by Wexner’s downfall. While some said it’s hard for them to square the man they know with the implications of the Epstein investigations, they also worry new revelations could further tarnish Wexner and embarrass the region.“With some people, particularly outside of Columbus, it’s all they’re going to know,” the community leader said. “It’s drip, drip, drip, drip, drip of guilt by association. It could be hard for anybody to actually explain the nature of the relationship or even understand it. I don’t know that anybody does.”