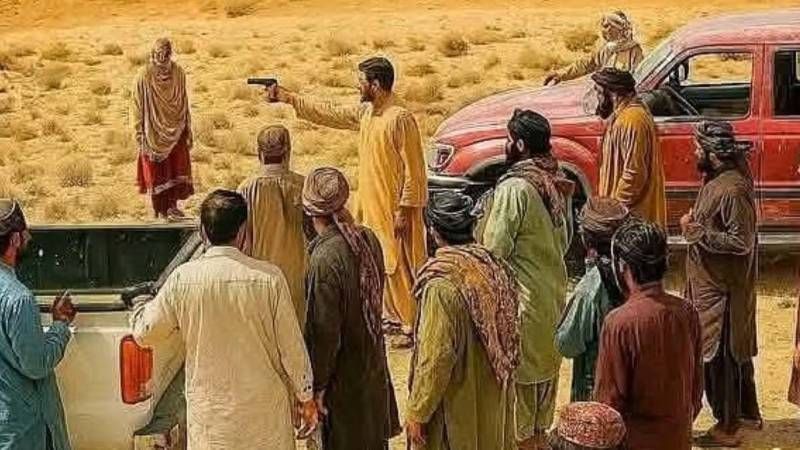

In the scorched emptiness of Margat, Balochistan, a woman clutched a Qur’an to her chest and spoke her final words. She stood facing a man from her tribe, asking him to walk seven steps with her before he fired. Moments later, she was shot in the back. Her husband lay beside her, riddled with bullets. Their execution was filmed, circulated, and consumed—not in secret, but as a message.This was not just a murder. It was a spectacle. And in Pakistan, it was nothing new.The video that surfaced a few days ago did not simply show an act of violence; it exposed an entire architecture of impunity. Behind the bullets were tribal decrees, centuries of patriarchy, a paralysed legal system, and a state that governs women’s lives only in theory. Thirteen men have since been arrested. An FIR has been filed. Ministers have condemned the act. But the story is far from over. In truth, it is barely the beginning.Pakistan has long suffered the plague of honour killings. Behind the sanitised term lies a brutal truth: women are murdered by their own families, their blood traded for reputation. In 2024 alone, more than 400 such cases were reported, according to the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP). Activists believe the real number is at least double. In provinces like Punjab, Sindh, and Balochistan, the pattern repeats with deadly consistency. Love is punished. Choice is criminalised. Daughters are executed.Yet the law, for all its promises, continues to look away. The 2016 Criminal Law Amendment was hailed as a breakthrough. It closed the legal loophole that allowed families to forgive murderers in the name of honour. Parliament vowed that such crimes would henceforth be punished with life imprisonment, regardless of reconciliation. But convictions remain rare. Trials stall. Witnesses disappear. Families retract statements. And the jirgas, though outlawed by the Supreme Court in 2019, continue to operate—ruling on love, marriage, and morality, as if the Constitution were an afterthought.In Margat, a tribal elder issued the death sentence. His authority came not from the Penal Code, but from a parallel order of social control. In Balochistan, where the state’s writ often travels slower than rumour, tribal justice still carries weight. The jirga is not a relic. It is a weapon. It functions with the state’s knowledge, if not its explicit blessing. And in regions long denied autonomy and development, it is treated as governance.This duality is no accident. The state, in its bid to suppress separatism and maintain stability in Balochistan, has for decades outsourced authority to tribal intermediaries. These men are rewarded with seats in parliament, leverage over land and resources, and silent consent to enforce their own codes. The price of this political pact is paid by women. In villages and deserts, in homes and halls, they are offered up to maintain order.The logic that underpins these crimes is older than the state itself. Women are viewed not as citizens but as commodities, transferred from father to husband. Their chastity is not personal, but communal. Their bodies are battlegrounds for male pride. Any deviation—a love marriage, a phone call, a photograph—is treated as rebellion. The punishment is not only death. It is erasure.The current legal regime has inherited these norms, not dismantled them. Colonial-era laws once allowed reduced sentences for men who killed in the heat of “grave and sudden provocation.” That same language, now entrenched in court reasoning, is still used to justify honour killings. Meanwhile, Zia-ul-Haq’s Islamisation policies embedded the notion of male guardianship into the fabric of law and culture. The Hudood Ordinances, the creation of Shariat benches, and the moral policing of women institutionalised gendered violence. That legacy remains intact.Even today, honour killings are rarely treated as premeditated murders. Prosecutors hesitate. Police treat cases as family matters. Investigations rely on familial cooperation that rarely comes. The law, technically present, is procedurally absent. What appears on paper is undone in practice.It is only when a video goes viral that the machinery stirs. When the public reacts, the state performs. Condemnations are issued. Committees are formed. Arrests are announced. But once the outrage fades, so too does the urgency. Justice, if pursued at all, becomes a formality. The victims are buried twice: once in shallow graves, and once in forgotten files.And so the cycle persists. From Farzana Parveen stoned outside Lahore High Court, to Qandeel Baloch strangled by her brother, to girls murdered in Kohistan over a wedding video. Each case promised reform. None delivered it. The mechanisms of violence remain, shielded by culture, silence, and impunity.To speak of honour in this context is to speak of a lie. There is no honour in control. No dignity in coercion. No tradition is worth preserving if it demands a woman’s life. Yet in the deserts of Balochistan, tradition still holds the gun.If Pakistan is to call itself a constitutional democracy, then it must act like one. The law must treat every honour killing as premeditated murder. All such cases must be initiated by the state, not the victim’s family. Jirgas must be criminalised without exception. Tribal leaders who order executions must face prosecution, not promotion. And women—especially those most at risk, those who choose their partners, those who speak online—must be protected not only by words, but by systems.To govern a nation is to protect its most vulnerable. If the state cannot do that, it ceases to be sovereign. It becomes complicit.There are no grey zones in this matter. Either women are equal citizens, or they are not. Either the law applies to all, or it applies to none. In Margat, the answer was clear. In the courts and corridors of power, it must be made so again. Not for the sake of image, but for the sanctity of life itself.(The author is a lawyer who holds an LLB (Hons) from the University of London. She is currently a law faculty member at LGS International Degree Programme and a research fellow at the Global Institute of Law)Courtesy: The Friday Times, Pakistanhttps://thefridaytimes.com/24-Jul-2025/murder-in-margat-when-honour-becomes-a-death-sentence