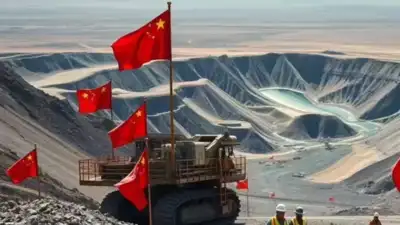

China’s export restrictions on rare earths have disrupted the global auto supply chain, forced production halts by carmakers, and pushed US President Donald Trump back to the negotiating table—but at home, the curbs have dealt a fresh blow to struggling Chinese magnet makers.Beijing imposed the restrictions in April in retaliation for US tariffs, severely impacting rare earth and magnet exports just as the domestic economy shows signs of weakness. Electric vehicles (EVs), a key end-use sector, are already facing headwinds, compounding the pain for magnet producers.According to a Reuters report, magnet exports plunged 75% in the two months following the export controls, and several global automakers were forced to pause production.

Although the US and China announced a deal on June 27 to restart rare earth trade flows, implementation is expected to take time.In a post on WeChat just 12 hours after the deal was announced, the state-backed Baotou Rare Earth Products Exchange said inventory was piling up in warehouses and warned that the damage would not be reversed quickly.The Baotou exchange, located in Inner Mongolia—one of China’s major rare earth hubs—described the impact in May as a “crisis” for domestic magnet producers.

Despite China producing 90% of the world’s rare earth magnets, export sales remain critical. In 2024, overseas sales accounted for between 18% and 50% of total revenue for the 11 largest publicly listed magnet firms, Reuters reported, citing public filings.“Their sales are now being squeezed from both ends – disrupted exports and flagging domestic demand,” said Ellie Saklatvala, head of metal pricing at commodities information firm Argus.

“They have temporarily lost an important part of their customer base, with no certainty about when they will regain it.”Two rare earth magnet producers told Reuters that revenue is expected to fall in 2025, though they declined to be named due to the sensitivity of the issue. One producer said the export curbs would have a “huge impact” on business, while small- and mid-sized players have already slashed production by around 15% in April and May, according to another source.Share prices rebound, but outlook remains grimMuch like US chipmaker Nvidia, Chinese rare earth firms are caught in the middle of geopolitical crossfire. After an initial share price crash in April, some listed magnet producers have bounced back—but analysts caution the rebound is not backed by industry fundamentals.“I can see various market outlooks, more or less negative depending on the assumptions, but none of them yield a sustainable rise in share price like we’re seeing,” said Cory Combs, head of critical minerals research at Trivium China.

He added that many players in the industry are private, limiting the insight that stock prices can offer.Magnet manufacturers are also under pressure at home due to a brutal EV price war, with automakers demanding price cuts from component suppliers. Complicating matters further is the customised nature of most magnet products, which makes them hard to resell domestically. Four sources told Reuters that producers are being forced to store unsold cargoes while they await export licences.Industry braces for long disruption and possible shakeoutSome companies have acknowledged the strain. Baotou Tianhe Magnetics Technology Co flagged potential export revenue risks in its annual report published in late April. Yantai Zhenghai Magnetics said last week that it had received export licences and operations were running normally, while deferring financial details to upcoming filings.However, analysts warn that rare earth trade flows are unlikely to return to pre-restriction levels any time soon.“Looking at China’s recent export controls on other critical minerals – such as antimony – it is clear that it can sometimes take longer than expected for exports to resume and normalise,” said Argus’ Saklatvala, quoted Reuters.China imposed similar export restrictions on germanium and antimony across 2023 and 2024. Despite being mostly used in civilian sectors, which theoretically face fewer licensing hurdles, exports have yet to fully recover, customs data shows.

Europe, for instance, is now receiving only a fraction of the antimony it once imported from China, leading to shortages for lead-acid battery manufacturers.David Abraham, an affiliate professor at Boise State University, said the export licence process now involves extensive documentation, leading to delays and added costs. “In some sense, there’s no going back,” he said.With the industry consisting of hundreds of manufacturers, the growing pressures could spark consolidation. “I do not know if Beijing sees that as a bad thing, because further consolidation is helpful for controlling and understanding where materials go,” Abraham added.

4 hours ago

1

4 hours ago

1

English (US) ·

English (US) ·