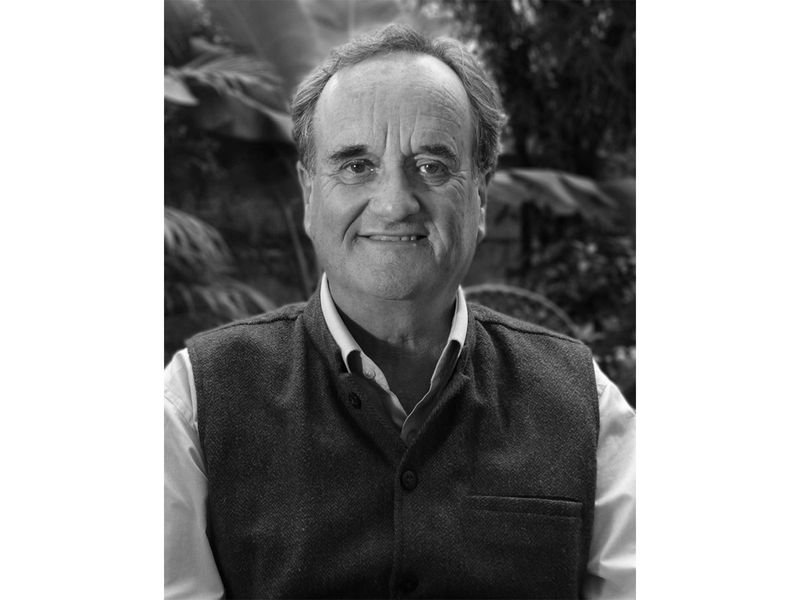

In the late 1980s, Mark Tully went to the Delhi Gymkhana Club wearing a pyjama-kurta. He was stopped at the entrance for ‘not being appropriately dressed’. The irony was delicious. Here was a pucca ‘gora sahib’, dressed as an Indian, being stopped from entering a club because he was not a ‘brown sahib’. In a sense, this incident illustrates quite aptly what Tully sahib was: a Britisher more Indian than many elite Indians themselves.With his passing away on January 25 at the age of 90, I have lost a friend of almost four decades and one of the finest journalists India—and the world—has seen.I first met Mark officially, as the pointsperson for foreign correspondents in the Ministry of External Affairs. But soon we became close friends, meeting often at my home or at his in Nizamuddin East, where he also had the then-rare commodity of Scotch whisky on offer.In India, Mark Tully was an institution. For as long as people can remember, the reports filed by him were the touchstone of balanced and authentic news. It was because of him that BBC Radio acquired such unprecedented traction in India. If you wanted to know what was really happening, you had to tune in to the BBC because Tully Saheb would tell you the truth.There are foreigners who visit India, and there are a rare few who are visited by India—entered, unsettled, and finally claimed by it. Tully belongs decisively to the latter category. To understand his life and work is to understand a certain kind of enlightened curiosity: patient, unshowy, and deeply respectful of complexity. He was not a man who sought to explain India by casually defining it, but one who allowed himself to be instructed by it, even when it resisted easy comprehension.Born in British India in 1936 in Kolkata, Tully’s earliest memories were shaped by the waning years of the British Raj. That inheritance could easily have become a burden—a lens clouded by nostalgia or superiority. Instead, Tully made a conscious and courageous choice to unlearn. When he returned to India as a journalist for the BBC, and later rose to become its bureau chief in New Delhi, he did so not as a custodian of imperial memory, but as a participant in an unfolding national story. India, for him, was not a posting. It was a vocation.What distinguished Tully from many foreign correspondents was not merely longevity—though his decades-long engagement is remarkable—but temperament. He was not a parachutist, dropping in during moments of crisis and departing with neat conclusions. He stayed. He listened. He learned, and this gave his journalism a texture that was at once intimate and incisive.During tumultuous periods—most notably the Emergency of 1975-77—Tully emerged as a lucid and credible observer. His reporting did not thunder with outrage, nor did it lapse into apologetics. Instead, it posed uncomfortable questions: how could a democracy so vibrantly argumentative acquiesce to authoritarian suspension? What did this episode reveal about the fragility, but also the resilience, of Indian institutions?Tully understood that India’s contradictions were not aberrations, but features of a civilisation negotiating modernity on its own terms. This sensibility found fuller expression in his books: No Full Stops in India, The Heart of India, and India in Slow Motion.These books are not exercises in foreign fascination. They are meditations on continuity and change, faith and politics, aspiration and disenchantment. Tully was particularly drawn to rural India—not as a romantic refuge from modernity, but as the crucible where its consequences are most starkly felt. He wrote of villages grappling with development, of religious belief persisting amid economic uncertainty, of moral worlds that could not be easily mapped onto Western categories.His deep sympathy for India did not mean indulgence. Tully could be unsparing about corruption, communalism, and the failures of governance. But his criticism was anchored in concern, not contempt. What I really liked about him was that even if he had a different opinion, he was not dogmatic but always open to discussion in a well-informed and non-shrill manner.In due course, I realised that he believed that India’s moral resources—its pluralism, its philosophical depth, its instinct for accommodation—were real, even if often under strain. This made him, paradoxically, more Indian in spirit than many who claimed the identity by birth alone.For Tully, India was home. This was not an act of rejection of Britain, but of affirmation of belonging to a place where he felt much more at home. Yet, what is noteworthy is that Tully’s Indianness was never performative. He did not don it like a costume or a rhetoric. It emerged organically, in his choice of friends, and in his lifelong companionship with Gillian Wright, a translator and authority in Indian literature.In this, Tully represents a vanishing species: the empathetic outsider. At a time when global commentary is increasingly biased or polarised, his voice reminds us of the value of patience, of humility before another civilisation, of the discipline of doubt. He showed that it is possible to love a country without mythologising it, and to criticise it without malice.His legacy, therefore, is not confined to journalism or literature. It lies in an attitude—a way of seeing India that is neither defensive nor dismissive. For Indians, especially, Tully’s work offers a mirror held by a friend: honest, steady, and quietly affectionate. In choosing India, he allowed India to choose him in return. And in that mutual recognition lies the enduring significance of Tully’s life and work.With his death, I have lost a true friend, and India a superlative chronicler of its times.— The writer is a former member of the Rajya Sabha