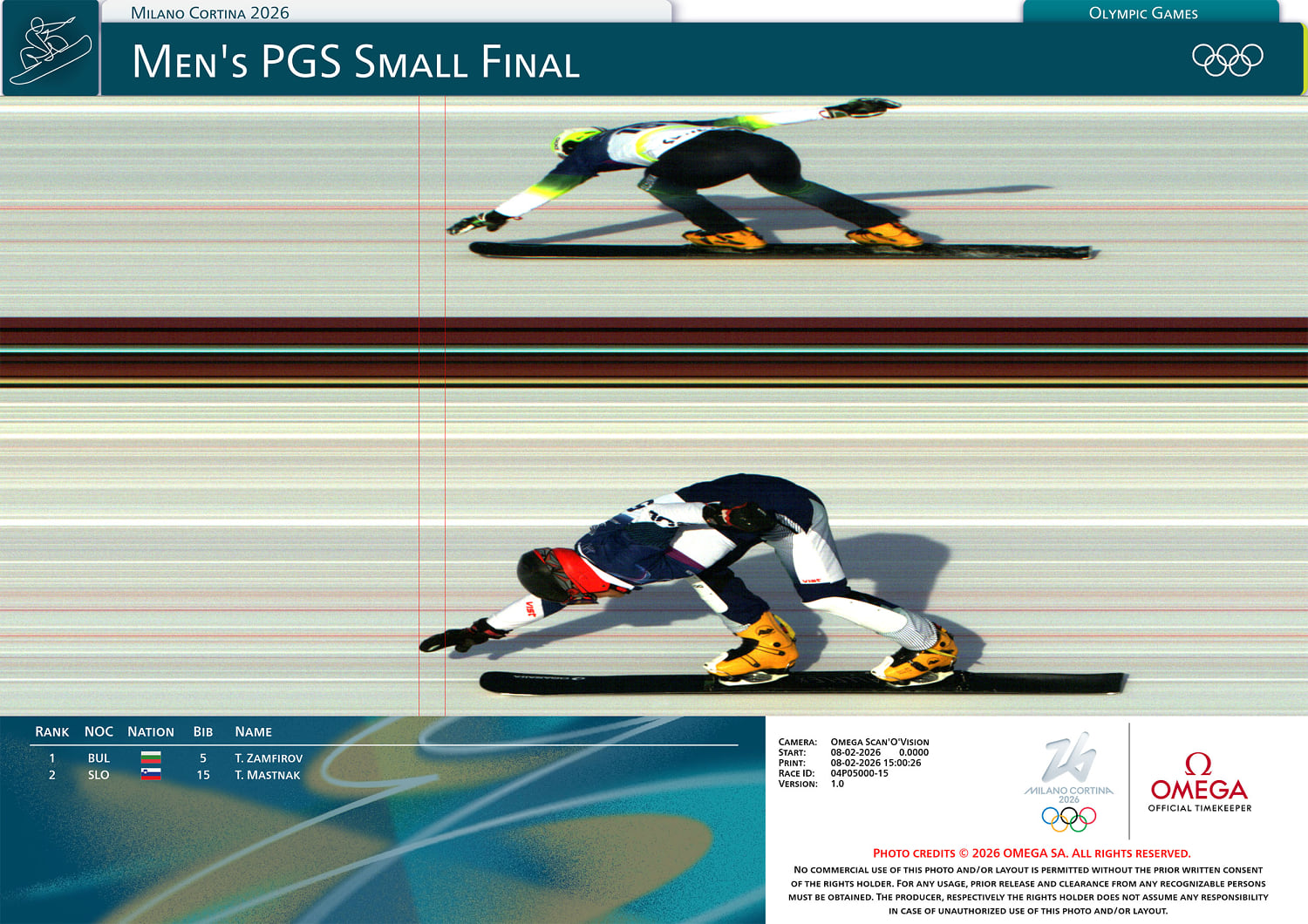

MILAN — Watching from the finish line, American skier Breezy Johnson was in first place of the women’s downhill Sunday when Germany’s Emma Aicher flew down the course in Cortina D’Ampezzo, gaining time on the leader.But almost as soon as the front of Aicher’s body crossed the finish line, triggering the timekeeping system to stop, Johnson knew she was in the clear. Instantly, scoreboards showed Aicher had finished in 1 minutes, 36.14 seconds — four-hundredths of a second behind. Johnson sighed and rubbed a hand over her head in relief. Johnson ultimately won and Aicher took the silver, their careers forever altered by that tiny difference determined by the most important team at the Olympics you don’t know about — the Omega timekeepers.”We take a lot of pride doing it but it also humbles us a lot,” said Alain Zobrist, the chief executive of Omega Timing. “We know that we can’t do any mistakes.”Since the Swiss timing giant sent employees with 30 stopwatches to Los Angeles for the 1932 Olympics, Omega’s business of keeping results at the Olympics has grown so large and sophisticated that a delegation from the company is already in Los Angeles preparing for the Olympics’ return in 2028. Omega introduced the “Magic Eye” slit photo finish camera at the 1948 Olympic Games in London. OmegaTheir work on these Milan Cortina Olympics began three years ago, Zobrist said. That level of planning stems from the baseline expectation of Omega’s job performance — every result must be perfect. In the most high-stakes moments, a photo finish, an operator looks at a monitor with footage from finish-line cameras shooting 40,000 photos per second. The operator then manually places a cursor where the athlete officially crosses the finish — it varies from sport to sport, from the front of the torso, to the front of the skate — to determine a time. By itself, the camera doesn’t take much time to learn how to operate, Zobrist said. “What you cannot learn is the pressure that comes with it when you operate it,” he said. “Think about the 100-meter final at the Summer Olympics, where billions of people are watching for and waiting for the results to appear as soon as the athletes cross the finish line. And you know as an operator that you’re not allowed to do any mistakes, because as soon as you push that enter button, the result is released and public.”At the 2014 Olympics, the men’s 1,500-meter speed skating final was decided by three-thousandths of a second — about a hundred times faster than the blink of an eye.”There is no contextualization from real life,” Zobrist said of a margin that small. “Because these tiny little margins you can’t see with your naked eye. It’s just too fast, so we need sophisticated camera technology to be able to capture those differences. Our cameras are taking about 40,000 pictures per second off that finish line to allow judges to have a very accurate understanding of who crossed the line first. Without this, no chance to see.”Omega’s systems can measure down to the millionth of a second, Zobrist said, but such detail isn’t needed, for now. Some sports require timing out to the hundredth of a second, others the thousandth.