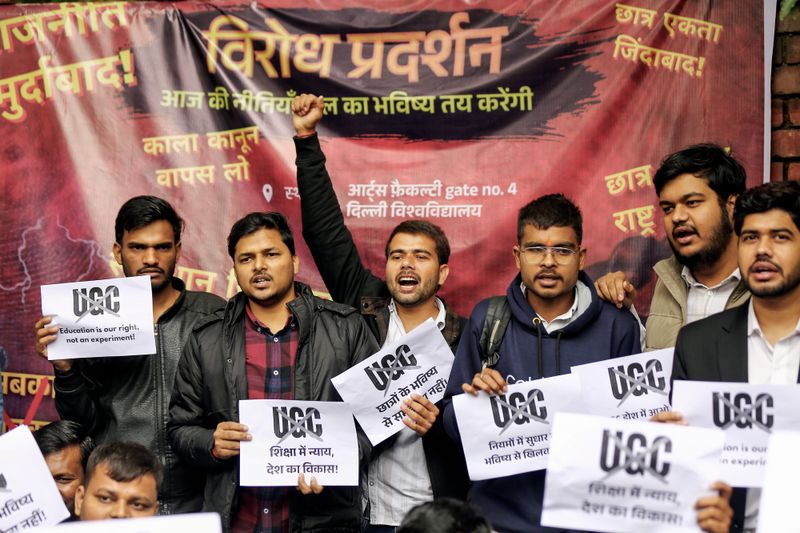

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has found itself in a political and social controversy over the University Grants Commission’s (UGC) newly notified caste equity rules.These regulations, formally called the University Grants Commission (Promotion of Equity in Higher Education Institutions) Regulations, 2026, aim to address caste-based discrimination on campuses and make anti-discrimination mechanisms enforceable.While the rules were framed with the stated intent of promoting equity and redressal for marginalised communities, they have drawn strong opposition, particularly from upper-caste groups, some of whom have traditionally been core supporters of the BJP. The backlash highlights both administrative and political challenges for the ruling party.Origins of the controversyThe roots of the dispute lie in a 2019 Supreme Court petition filed by the mothers of Rohith Vemula and Payal Tadvi, both of whom were students who tragically died by suicide, alleging caste-based discrimination in their respective institutions. Their petition argued that the UGC’s 2012 anti-discrimination framework was ineffective because it lacked enforcement mechanisms. In response, the Supreme Court, in January 2025, said that anti-discrimination rules must be “more than symbolic” and required the UGC to make its framework enforceable. The 2012 regulations had provided protection only to Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs).Following this directive, the UGC published draft regulations in February 2025, inviting public feedback. Notably, the draft did not include Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in the scope of caste discrimination or mandate their representation on campus equity committees. However, after recommendations by a parliamentary standing committee on education in December 2025, chaired by Congress MP Digvijaya Singh, the final regulations notified on January 13, 2026, expanded the definition of caste-based discrimination to include OBCs.Key features of the UGC’s new rulesThe regulations establish a comprehensive three-tier structure to address discrimination on campuses:Equal Opportunity Centres to oversee institutional policies.Equity Committees to investigate complaints, consisting of 10 members with at least five from reserved categories (SC, ST, OBC, women, persons with disabilities). The committee must meet within 24 hours of a complaint, submit a report in 15 days, and ensure action within seven days.Mobile Equity Squads and Equity Ambassadors to monitor, prevent, and create awareness about discrimination.The rules also establish an Equity Helpline for reporting incidents. Institutions failing to comply face punitive actions, including being barred from UGC schemes and grants. Crucially, the rules allow complaints to be made confidentially but do not provide anonymity for the accused during preliminary enquiries. Moreover, the regulations have removed provisions penalising false complaints, which were part of the February 2025 draft.Why the BJP is facing backlashPerceived bias against upper castesThe expansion to include OBCs and the mandatory composition of committees excluding general category members has been interpreted by many upper-caste groups as discriminatory against them. Critics argue that the rules create structural disadvantages for the general category, giving disproportionate power to reserved groups in equity committees. This has triggered a sense of alienation among the BJP’s traditional upper-caste voter base, particularly in states like Uttar Pradesh.Deviation from Supreme Court’s original intentThe Supreme Court’s 2025 judgment directed the UGC to make the 2012 rules enforceable, which originally applied only to SCs and STs. By extending protections to OBCs, some argue that the UGC exceeded its mandate. This perception of overreach has fueled opposition from both the public and within political circles.Removal of safeguards against misuseThe elimination of penalties for false complaints has been a major point of contention. Critics fear that students could be accused maliciously, jeopardizing their careers without accountability for the complainant. Similarly, the lack of procedural safeguards for the accused, such as anonymity during investigations, has raised concerns about reputational damage.Political implications for BJPThe BJP faces a delicate situation because it is politically associated with upper-caste groups, particularly Brahmins and other general category communities. More than a dozen local BJP leaders in Uttar Pradesh have resigned, arguing that the rules are one-sided and anti-upper caste. Given that Uttar Pradesh goes to assembly elections next year, this backlash has significant electoral implications. The party risks alienating a core vote bank while appearing to favor OBCs and SC/STs.Wider protests and political falloutProtests have spread to multiple cities, including New Delhi, Jaipur, Patna, Indore, Ranchi, and Chandigarh. Even within the BJP, there is a visible unease: while Union Education Minister Dharmendra Pradhan stated that misuse would not be tolerated, other leaders like MoS Home Affairs Nityanand Rai avoided commenting, reflecting the internal tension.Perception of polarisationThe structure of the new rules, mandating reserved category representation and rapid timelines for investigation, is seen by critics as potentially divisive. By placing upper-caste students and faculty in a position of relative vulnerability in equity investigations, the regulations may inadvertently reinforce caste-based fault lines on campuses. Analysts argue that in a politically sensitive country like India, such perceptions carry weight beyond the educational sphere, affecting public opinion and voter sentiment.ConclusionThe BJP’s predicament over the UGC caste equity rules stems from a complex mix of legal, administrative, and political factors. Legally, the UGC acted under Supreme Court guidance but expanded the scope of protections to include OBCs, leading to perceptions of overreach. Administratively, the rules impose stringent timelines, discretionary powers, and lack safeguards for the accused, raising concerns about fairness. Politically, the regulations risk alienating the BJP’s traditional upper-caste base while attempting to maintain its outreach to OBCs and Dalits.In essence, the party is caught between the Supreme Court’s mandate, the UGC’s expanded interpretation, and the social and electoral sensitivities of caste dynamics. The backlash underscores the delicate balancing act required in Indian politics when addressing caste-based equity: policies intended to promote inclusivity can sometimes trigger perceptions of exclusion, especially among groups historically aligned with the ruling party.